Chapter 27

Interpreting Your Soil Test

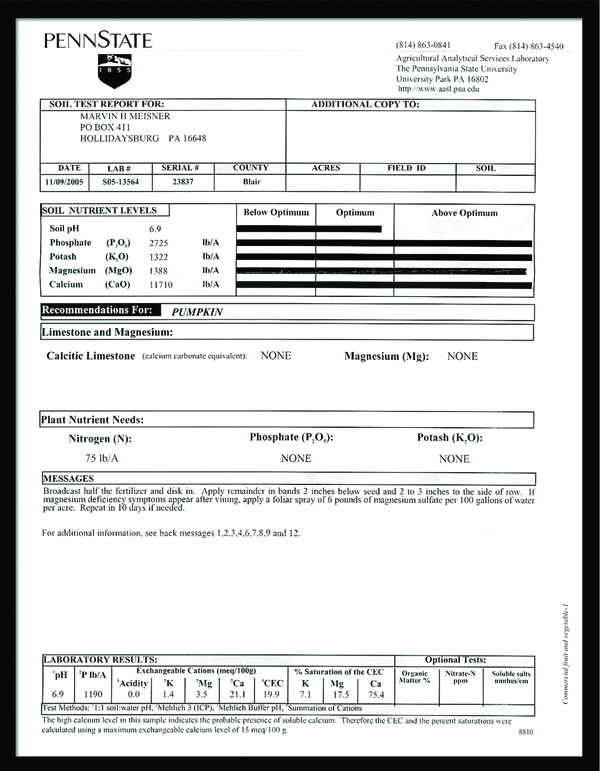

A soil test looks at the chemical status of your soil. The report shows the pH (degree of acidity/alkalinity), and the available amounts of various plant nutrients that were present in your soil at the time of sampling. Some soil tests also report total organic matter present in the soil. The soil test report is an index of chemical soil fertility. A grower who adds large amounts of organic matter to his garden should be keenly interested in soil pH. Tomatoes do best in a pH of 6.2 to 6.8.

Soil Sampling

Obtaining a soil sample that is representative of your entire garden is important if the test results are to be useful. The best time to get a soil sample is in the late fall after your garden has been "put away," or in the early spring before you have added anything to it. Collect a soil sample by taking samples 1 to 6 inches deep from at least ten areas scattered throughout your garden. If you have just roto-tilled the garden, you may take samples from the surface. Otherwise, dig a hole about 8 inches deep with a shovel, and use a trowel to take a small, even slice of soil from a 1 to 6 inch depth. Mix together all of the samples in a clean plastic bucket so as not to have any contamination. Allow the combined sample to dry for several days at room temperature. If there is a lot of organic matter in the sample, put it through a screen to remove the larger particles. Then put a scoop of the soil sample in the bag provided by the testing lab, or a ziplock plastic bag, and mail it to the lab along with your instructions.

Usually, the laboratory will report each nutrient in parts per million (ppm) or pounds per acre (lbs./acre) or both. These numbers give an approximation of the nutrients in your soil that are available to the plants, but not the total amount of each element in the soil. The test results will not tell you what will be available when the organic matter in your soil is broken down by soil organisms.

Most labs will follow the numbers for each nutrient with a letter code as follows: VL = very low (critically deficient); L = low (likely to restrict crop yield); M = medium (sufficient for most crops, may be limiting to heavy feeders); H = high (favorable); and VH = very high (ample, possibly excessive). Any nutrients that are rated VL or L on your soil test need to be supplemented, whereas nutrients rated VH may indicate a need to cut back on inputs of those elements.

Direct measurements of soluble soil nitrogen (N) are often misleading, as this element can fluctuate wildly between nearly undetectable and excessive levels within a single season. Therefore, many labs do not report N, but do give an estimated nitrogen release (ENR) in lbs./acre-year, based on the soil's organic matter content and texture. If the ENR is 120 or more, the organic matter will provide most or all the N needed by most crops. Our local laboratory does not routinely report nitrogen levels, but gives a recommendation for adding chemical fertilizer each spring based on expected crop needs.

The soil test will also report pH. A pH of 7.0 is neutral; 6.0 is mildly acid, 5.0 is strongly acid, and 4.0 is extremely acid. Numbers above 7 indicate alkaline soil. Tomatoes prefer a pH of 6.2 to 6.8, (slightly acid) although they will thrive at anywhere from 5.8 to 7.3 if ample organic matter is present.

A soil test usually includes a measurement of organic matter content, given as a percentage of the total sample. If you are adding large amounts of leaf compost and manure to your soil each year, it is highly likely that you have sufficient organic material. An organic matter content of 10% is adequate for tomatoes, but if the number is higher, don't be concerned.

Most labs also report the cation exchange capacity (CEC) of the soil. This is an estimate of the soil's ability to hold positively charged nutrients in a form available to plants, especially K, Ca, Mg, and Na. The soil's CEC is related to its clay and humus content. Rich, clay-loam soils will have a high CEC, and dry sandy soils will have a low CEC. The higher the CEC, the better.

Most laboratories give recommendations for increasing the nutrient content of your soil if it is low. You can convert their recommendations to organic amounts, or make your own recommendations by using some of the information below. It is better to try to correct your soil deficiencies over several years rather than all at once as usually recommended in most reports.

Acidity (pH below 6.0): Use agricultural limestone to raise pH. If the soil is rated L or M in calcium, but H or VH in magnesium, use high calcium lime. If magnesium is also L or M, use dolomitic limestone (high magnesium lime).

Alkalinity (pH 7.5 or above): Use organic mulch such as tree leaves, pine straw, or chipped brush. For strong alkalinity, use elemental sulfur at 5 to 10 pounds per 1,000 square feet.

Low organic matter: Use generous amounts of compost, 250 to 1000 pounds per 1000 square feet. You may need an organic N-P-K fertilizer to obtain satisfactory crop yields at first. Grow a green manure cover crop (winter rye, red clover, peas, beans, etc.), or apply composted manure as a mulch. Foliar feed with fish emulsion and/or seaweed.

Phosphorus: If P is low, supplement it with colloidal phosphate or rock phosphate at 12 to 20 pounds per 1,000 square feet. Also apply some high quality composted leaves and manure.

Potassium: If K is low, it can be supplemented with manure-compost, and hay-mulch, both of which are rich in K. Potassium sulfate and greensand are two mineral amendments that add K. Beware though, if K gets very high it can make the soil sticky, upset plant nutrition, or reduce vegetable quality. Cut back on the use of hay mulch and manure compost until K is reduced.

Calcium: If Ca is low but pH is optimal or high, use gypsum at 7 to 10 pounds per 1000 square feet once or twice a year until soil tests indicate that Ca levels are medium to high.

Magnesium: If Mg is low but pH is optimal or high, use Epsom salts at 5 to 7 pounds per 1,000 square feet and retest the soil in a year to see if more is needed.

Sulfur: If S is well below optimum (10 ppm or lower), use gypsum at 20 pounds per 1000 square feet.

Micronutrients: Micronutrients are expensive to test for, and should not be a problem if organic matter is being added to the garden regularly. Only in the event that the garden is doing poorly would these be worthwhile measuring.

For tomato growers using lots of organic matter in their garden, pH is the most important test being performed. The correction of any soil deficiency, unless it is producing catastrophic results, should be performed slowly and gradually over several years to insure against drastically altering the pH.